International Centre for Water Cooperation (ICWC)

The ICWC is a collaboration between SIWI, UNESCO, and the Swedish Government. The centre generates and shares knowledge on water cooperation, and contributes to context-specific solutions for cooperation over shared freshwater resources.

International Centre for Water Cooperation

Why focus on water cooperation?

According to the IPCC (2022) roughly half of the world’s population experiences severe water scarcity for at least part of the year. And this is only set to increase as climate change exacerbates already fragile conditions. Jointly managing shared water resources is proven to alleviate a region's vulnerability to extreme water challenges.

Read more about water cooperation

Water cooperation preparedness index (WCPI)

The WCPI was specifically developed for the Initiative to assess a country’s level of water cooperation preparedness. The index combines 70 indicators with existing global data relating to water policy and practice at the national and subnational levels. This unique combination of data determines the degree to which conditions within a country are favourable for water cooperation across sectors, levels, and stakeholders.

The indicators fall within one of five identified factors of cooperation that make up the assessment framework: governance, leadership, data and information, financing and investment, and enabling conditions. Countries with high WCPI scores are expected to have conditions in place that can enable cooperation in different ways through:

- having governance systems in place that can promote coordination and participation;

- having proactive and responsive leadership that facilitates cooperation by developing national policy frameworks and processes linked to integrated approaches and equity;

- giving high priority to developing and sharing data and information;

- giving high priority to investing in water cooperation and participation; and

- having more peaceful conditions against which cooperation can take place.

A country's WCPI can inform national level policy priorities

The WCPI provides indicative data that can inform national level policy priorities related to water cooperation. The results of this assessment and the framework used can be the starting point for in-depth investigations of water cooperation in national and sub-national contexts. Indeed, a recommendation to national governments is to carry out detailed assessments to map their country’s water cooperation preparedness across the different factors of cooperation.

There is no one-size-fits all approach to improving water cooperation, meaning that it is important to map existing strengths and weaknesses to be able to set priorities for improvement. The WCPI data and the framework presented in this report could serve as an entry-point for such assessments, but they should be adapted to the specific country context. By carrying out such national assessments it becomes possible to pinpoint specific factors that facilitate and inhibit water cooperation in the country in question. This in turn can help to direct attention and resources to the right place.

Overall, the WCPI should be seen – in its current form – as giving an approximate indication of countries’ water cooperation preparedness, and not as an exact measurement tool.

A note on data used and methodology

The data for the indicators within the governance, leadership, data and information, and financing and investment categories come from the SDG reporting data for SDGs 6.5.1[1] and 6.5.2[2], and from UN-Water/WHO’s Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking Water (GLAAS).[3] The enabling condition category a variable based on the Global Peace Index (GPI).[4] Since the data from these various sources stem from different years, and to facilitate the inclusion of data for as many countries as possible, the WCPI is based on data from the multiple-year period of 2018 to 2022.[5] It is important to stress that all data except that for the enabling environment category is self-reported by governments. The ways in which different governments collect, verify, and report this data are likely to vary greatly. For these reasons, as well as the use of mean substitution to fill data gaps, caution needs to be applied in comparing scores.

[1] Accessible through: http://iwrmdataportal.unepdhi.org/country-reports.

[2] Accessible through: https://sdg6data.org/index.php/en/tables.

[3] Accessible through: https://glaas.who.int/glaas/data.

[4] Institute for Economics & Peace, ‘Global Peace Index 2022: Measuring Peace in a Complex World’ (Sydney, June 2022), http://visionofhumanity.org/resources.

[5] GLAAS data from 2018 and 2021, SDG 6.5.1 and 6.5.2 from 2020 (except SDG 6.5.2 data for Bolivia, which is from 2022), and GPI from 2022 (except where adjusted HDI data was used, this comes from 2021).

Global Water Cooperation at a glance

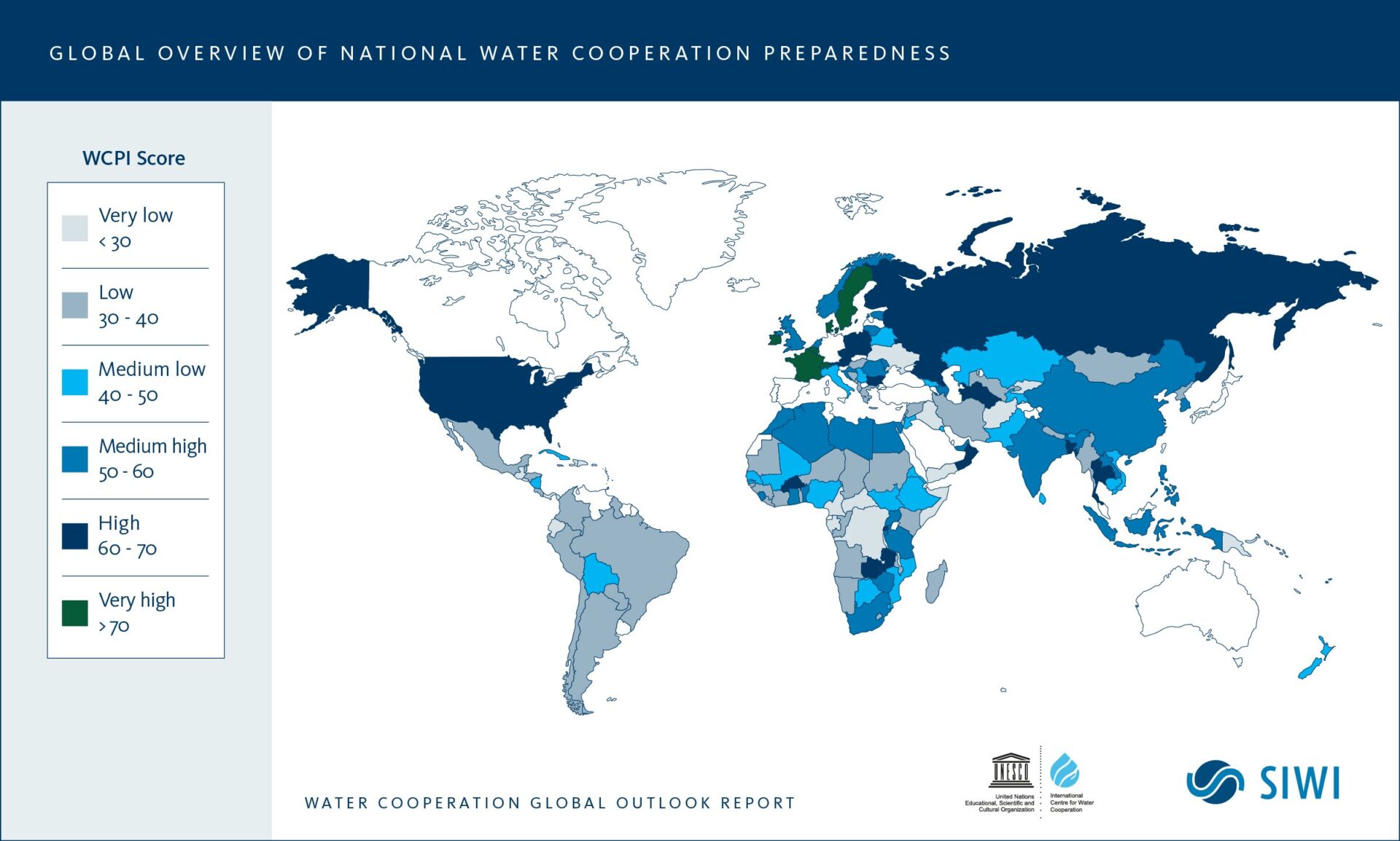

The WCPI scores are divided into six categories of preparedness, ranging from very low to very high, each category having its own colour. The map below clearly shows that countries vary substantially in their water cooperation preparedness, and that the world is facing a water cooperation deficit. For example:

- The average level of water cooperation preparedness across all countries surveyed is medium low (the median WCPI score is 45 and the mean score is 47, both falling within the medium low score group)

- Nearly 320 million people live in countries with a very low WCPI score, with a further 740 million living in countries with a low score.

- The most common preparedness scores are low (35 countries), medium low (33 countries) and medium high (35 countries).

- At the highest end of the scale, only 9 out of 149 countries fall within the very high score group. These are all located in Europe.

- On the bottom end of the index, the number of countries scoring very low is a lot higher, at 17. This group of countries is geographically a lot more diverse than the group with very high scores, with at least one country in each region having a very low cooperation preparedness score.

The results show that water cooperation preparedness is still relatively low in much of the world. Though whilst it should be noted that cooperation preparedness does not translate directly into actual cooperation, the two do somewhat correlate, showing that much more should be done to foster increased cooperation on water issues within countries with a low score. The WCPI data helps highlight countries where increased efforts might be necessary, although additional context-specific analysis is essential for understanding the actual situation on the ground.

The following interactive maps show the assessed countries’ WCPI scores in more detail. Clicking on a country will reveal deeper insight into the specific breakdown of the WCPI score, and which of the five factors the country had the strongest and weakest ratings.

In Africa, water cooperation preparedness is similar to the global average, both when taken as a whole as well as for each of the factors of cooperation individually. There are large differences within the region, which manifest both between and within subregions. In some subregions the differences between countries are relatively small, whereas in others they are more substantial.

Cooperation preparedness in the Americas, as measured through the WCPI, is below the global average. The region’s average scores are below average for each of the five individual factors of cooperation, with the exception of the enabling environment. However, since data for much of the countries in this region was missing the picture is incomplete, particularly for the Caribbean. Nonetheless, the available data shows that the Americas region contains some of the lowest WCPI scores globally, as well as some countries with scores close to the average, and also some with relatively high scores.

Water cooperation preparedness in Asia is similar to the global average. Its scores are around the global average for all factors of cooperation apart from data and information, for which the score is somewhat below average. There are large differences between countries in the region. Unlike in Europe, these differences do not manifest themselves between subregions; instead, differences between countries in the same subregion are often large.

Europe is the region with the highest average water cooperation preparedness, which manifests itself across all factors of cooperation. There is substantial variation across countries and from one subregion to another, however. Western Europe has the highest average preparedness of all subregions worldwide, but some European countries perform significantly under the global average.

Cooperation preparedness in Oceania is below the global average. The region’s average scores for each of the five individual factors of cooperation, except the enabling environment, are all either somewhat or clearly below the global average. The within-region variation is small. Data was unavailable for the majority of countries in this region, however, meaning that the picture is incomplete.

Other points to note include:

Least Developed Countries (LDCs) on average have a water cooperation preparedness score slightly below the global average. Looking at the individual factors of cooperation, they score around average on governance, leadership, and data and information. The scores for the enabling environment and especially the financing and investment factors are below the global average, however.

The average cooperation preparedness in Small Island Developing States (SIDs) is below the global average. With the exception of the enabling conditions, the region’s averages for all the other factors of cooperation are either somewhat or (in the case of financing and investment) clearly below the global average.

For both the LDC and SIDS country groupings, it should be noted that some countries within them do have relatively high levels of water cooperation preparedness. These might hold some of the keys to best practices for other LDCs and SIDS to improve conditions for water cooperation. Identification of such best practices and considering them as options for use in other places, where conditions seem suitable, may be advisable.

International Centre for Water Cooperation

The International Centre for Water Cooperation generates and shares knowledge on water cooperation, and contributes to context-specific solutions for cooperation over shared freshwater resources.

Find out more